It’s likely no surprise to art aficionados that an extraordinary exhibit has opened at the Art Institute of Chicago this summer.

Chicagoans don’t question an oft used phrase referring to the Art Institute as a world class museum. Arguably, among the things that have made it so in their minds are its large collection of French Impressionists and such famed paintings as Grant Wood’s “American Gothic,” Edward Hopper’s “Nighhawks,” Pablo Picasso’s “The Old Guitarist” and Georges Seurat’s “A Sunday on La Grande Jatte — 1884.”

But a great institution does more than collect. It investigates well-known works were created and why and also presents new and lesser known works.

There was “Seurat and the Making of ‘La Grande Jatte’ ” back in the summer of 2004 which revealed other figures in the famous painting and included related sketches and paintings.

Then there was “Matisse: Radical Invention 1913-1917” in spring of 2010 which revealed new information about “Bathers by a River -1909-1910” found through technical research. It also offered a more in-depth view of the artist’s works.

More recently, the museum focused on the paintings: “Van Gogh’s Bedrooms” which were researched and compared in order to shed more light on the artist and his time in Arles.

Visitors at that exhibit in 2016 may remember that Van Gogh set aside a room for Gauguin whom he greatly admired and hoped would help start an artists’ commune there.

Now the museum is turning its spotlight and technical research onto Gauguin. The resulting exhibit sheds extraordinary light onto an artist who is much more than a painter particularly fond of Tahitian figures.

The kernel from which the current Gauguin exhibit grew came more than five years ago when the Art Institute acquired a cabinet he collaborated on with Emile Bernard, and later on, a vase by Gauguin was also acquired, according to Research Associate for European Painting and Sculpture Allison Perelman.

During a phone interview, Pereleman explained that while doing research for an online catalogue the findings evolved into a major exhibit that went far beyond showing two dimensional works of paintings and works on paper.

“The technical and other research really opened our eyes to Gauguin’s other media. We wanted to tell the story,” Perelman said.

The story is revealed through ceramics, wood carvings, decorated items, prints and paintings in Regenstein Hall.

What you can read into the items is that Gauguin saw artistic possibilities in everyday objects and that he enjoyed experimenting with materials and shaping unexpected forms.

You also learn that Gaugin, a former merchant marine, liked to move around. He needed a change in environs to spark creativity even if leaving where he was meant returning to a place previously visited.

He also sought out communities that either kept old traditions as with Brittany or he that he thought might still be untouched by colonization such as Tahiti. It didn’t so he created what he thought it should be.

The best way to understand the exhibit is to pick up the audio player. You can also download the Art Institute’s app then listen to the tour on your I Phone for free.

The voices you’ll hear are exhibit curator Gloria Gloom, Chair of the European Painting and Sculpture Department and Perelman. They carefully chose just a few items that explain a particular bent, interest or change in Gauguin’s work.

Right from the first gallery you will be encouraged to look closer at the objects.

Hear, look and see a box that has ballet figures on one side and Chinese masks carved on the other. Inside is a mummy carved by Gauguin.

“I think it was inspired by the sarcophaguses Gauguin saw in museums when he lived in Copenhagen,” Perelman said. She found it interesting that Gauguin rendered the box “functionless” as a container. ‘It teases,” she said.

She also pointed out that Gauguin’s ceramics might look usable but they weren’t.

“He called them sculptures. The vase cannot hold water. It would leak. And the handles on other pieces would break if someone tried to pick them up,” Perelman said.

She added, “This is the largest presentation of his ceramics.”

Walk around the ceramics instead of merely reading their labels and viewing them from one angle. That way you might catch some of the images that Gauguin repeats throughout his works.

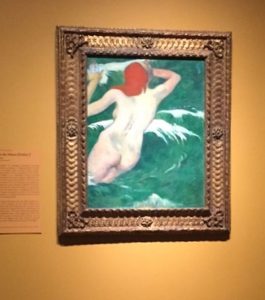

In one of the galleries you will see “In the Waves (Ondine l),” a gorgeous painting of a red-headed woman enjoying the water. She is repeated in several works but not always recognizable.

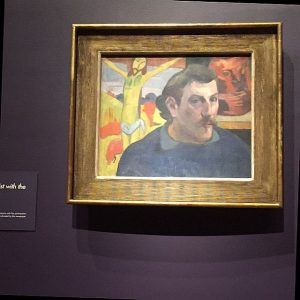

Gauguin also liked to include images in his paintings not particularly related to the main subject. In a painting where he put himself with his “Yellow Christ” he also included a ceramic piece in the top right-hand corner.

Perelman thinks the color reflects on his visit with Van Gogh in 1888 and a color favored by modern artists of the time. He painted “Yellow Christ” in 1889.

“I don’t think it’s a coincidence that he used yellow. He also used it for his prints,” Pereleman said.

Speaking of prints, take time to look at his wood blocks and print making process. Gauguin liked to work with wood in sculptures, print making and tools.

Time is what is needed to see and appreciate the 240 items in the exhibit. And if you watched the videos on how Gauguin worked in different media, you probably have a better idea at the end of why the exhibit is titled “Gauguin: Artist as Alchemist.”

The exhibit is at the Art Institute of Chicago, 111 S. Michigan Ave, Chicago, now through Sept. 10, 2017. For tickets and hours call (312) 443-3600 and visit AIC.