John D. of Standard Oil Co. fame and son, John D. “Junior” of Rockefeller Center note, are the philanthropists and personages who often come to mind when the name Rockefeller is said.

But mention Edith, daughter of John D. Senior, and the reaction is likely to elicit a blank. However, Edith who grew up in a household that only favored the male side in education and business, is worth knowing.

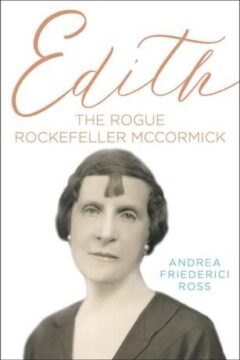

In her recently published book, Edith: The Rogue Rockefeller McCormick, Andrea Friederici Ross uncovers a woman who in spite of lack of family support and appreciation, learned several languages so she could study philosophy and psychiatry as originally written. She passed along the teachings of Carl Jung.

Edith became a patron of the arts with husband Harold McCormick (son of Cyrus McCormick) that included the Chicago Grand Opera, a company that predated the Lyric. She was also instrumental in forming the Krenn & Dato real estate company and founding Brookfield Zoo.

It was the Brookfield property that started Ross on her “Edith” journey about 10 years ago.

“I became interested in Edith when I wrote Brookfield Zoo’s history book Let the Lions Roar, because she donated the land that started the zoo. In fact, the first line of that book is “An unusual woman made Brookfield Zoo possible,” Ross said during an email-interview.

“Unusual woman” is only a hint to whom readers will meet in the book. It is filled with family members and recipients of her patronage who have their own views of Edith and her spending. She acquired costly jewels and antiques but was also interested in affordable housing for young, first-time home buyers.

Readers may well believe some of her actions are the result of what is considered expected of a wealthy woman. The book reveals Edith’s and her family’s ideas on women’s and men’s places in society that may explain the neuroses that plagued her and other family members.

When asked about indications of Edith’s inner feelings when researching her subject’s life and times, Ross said, “For Edith, duty was front and foremost. Whereas in her childhood it was duty to God and parents, Edith later internalized that to be duty to society (entertaining, spending, employing, underwriting). I, personally, do not believe she ever allowed herself to fully experience her emotions.”

The book mentions that Edith believed she was part of King Tut’s life in an earlier incarnation. After reading Edith: The Rogue Rockefeller McCormick, I wonder what or whom she would like to be if she could come back during the 2020s when women appear to be doing better in the gender-discrimination battle.

Some Chicago Edith connections

North of Chicago lies an upscale Lake Forest, IL subdivision known as Villa Turicum. The entry street off Sheridan Road is McCormick Drive. A short way in is Rockefeller Road. Villa Turicum was the 300-acre Italianate summer estate of Edith Rockefeller McCormick.

Nearby is an approximately 200 acre Highland Park, IL neighborhood north of IL Rte 22 known as the Highlands where there are Krenn and Dato Avenues. Edith’s longtime friend, Edwin Krenn, and Edward Dato, formed Krenn & Dato, a highly successful, nationally known real estate business backed by Edith until it over expanded.

Edith: The Rogue Rockefeller McCormick by Andrea Friederici Ross, (Southern Illinois University Press, 2020, $29.95).

Jodie Jacobs